**** out of ****

**** out of ****

“Joyeux Noël” is a French film that inspires and promotes the idea of brotherhood, an important theme that not only relates to the fraternity of human beings, but also rejects war as a medium of resisting it. This anti-war sentiment is implied through many images in the film, which suggest the dehumanization and stupidity of men who enter the conditions of war. On the other hand, the other scenes insist on the brotherhood that men can derive whenever they realize that they are all the same. These themes are interpreted through an array of incredible stylistic and structural aspects under the direction of Christian Carion, actualizing “Joyeux Noël” as a modern French anti-war masterpiece.

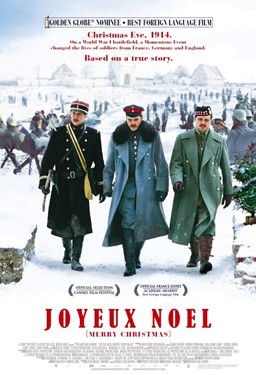

“Joyeux Noël” centers on the real-life Christmas truce between the French, the Scottish, and the Germans during World War I and portrays characters such as the German tenor, Nikolaus Sprink (Benno Fürmann), his Danish opera star lover, Anna Sörensen (Diane Kruger), the German lieutenant, Horstmayer (Daniel Brühl), and the French Lieutenant, Audebert (Guillaume Canet), to encapsulate the humanity essential to its thematic heart. The film then depicts the events that follow as the characters and the three companies of soldiers share humanity in the crucial time of peace.

The structure of this film is perfect; “Joyeux Noël” readily combines many typical war-related thematic elements in a fresh way while featuring a great script and wonderful story. Christian Carion ably directs the film with a sense of pride that should leave viewers enchanted and interested during the Christmas cease fire. In addition, many stylistic aspects, such as lighting, sound, editing, and cinematography, blend perfectly together to achieve the conditions of war or of peace.

The film offers several examples that evoke the harmful effects of war, and the first example establishes a correlation between those effects and children. The opening scene features a slow dolly shot that moves toward children explaining WWI. This establishment stimulates questions of war’s effects on children, which leads viewers to realize the effects of war on younger generations. Because of the superimposition of each new child over the next, it’s like the same child speaking, though his appearance changes and his speech represents a different language. This clearly underlines the human aspect of the film. Later in the scene, the long dolly shot passes through the map in the room, and an aerial shot rushes over lands with exceptionally slight differences but notable similarities. In essence, the shot unites those lands, contending that on some level, even the land on which humans live is the same.

Death is always a consequence of war, and the film establishes that connection quickly. Death is highlighted when the Scottish man opens the door of the church at the beginning of the film, extinguishing all of the flames the priest had lit. Using a selective focus, the shot foreshadows the death (or the extinguishment) of men who go to war and prompts the overall negative view of war in general. On the other hand, that particular shot of smoking candles fades to lit candles in another room while a diva sings an operatic tune. Its implications define music as life and signify its importance in comparison to war, which explicitly infers death.

In addition to death, the film wants to implicate several more negative consequences of war for viewers, including chaos and the dehumanization of man. During the great battle early in the film, a handheld camera captures a tracking shot of the men in the trenches and on the battle and exposes the great realities of the war, particularly on the chaos involved. Using a weepy orchestral piece over the battle, the scene prominently features quick cuts and intensely loud sound effects amidst the chaos. In fact, one important attribute of the scene is crosscutting that includes shots of men and their artillery, comparing one to the other, signifying that in war, man is like, or less than, his machine. The machine robs him of his humanity and turns him into a less than human object.

The film juxtaposes war to Christmas in different ways, but intentionally to promote the concepts of peace and brotherhood. As the eve before Christmas falls, the soldiers are in their respective trenches as a Scotsman’s bagpipes erupt over the crystal silence. While he plays, the German opera stars begin to sing “Silent Night” against his song, in a sort of “battle” between the two. Eventually, the Scotsman plays the song while the Germans sing, uniting the two and creating the harmony that is essential to the film. There are several instances of two different musical cultures being united in the film, and the codes implied by their unity indicate the brotherhood significant to the film. Finally, another effect of Christmas is when Sprink crosses the snowy battlefield in an extra long shot, singing and carrying the Germans’ Christmas tree; the action of singing connects back to the idea of life while the tree becomes a symbol of peace and unity.

While incredibly dramatic and mind-opening, the film does contain some humorous elements, such as Felix/Nestor, the cat who prances through both trenches like a double agent while signifying how he is the same cat no matter what name he has. Even this one example signals the critical theme of “Joyeux Noël”: We are all the same but with different names, and thanks to brotherhood, peace can be attained. While one of endless anti-war films out there and unlike classic films like “Paths of Glory,” which is more in-your-face in its protests, essentially, Christian Carion’s “Joyeux Noël” succeeds in its propagation of peace and will surely become a film classic in years to come.

April 20, 2008

Joyeux Noël (Merry Christmas)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment