**** out of ****

**** out of ****

“The Tin Drum” is a controversial, lengthy German epic that boldly pushes viewers to see how much they will react. Graphic sexuality, intense shots, and a disturbing story are but a few of the shocking and visceral features that are embodied in this uncanny, surreal World War II story.

In the film, a young boy named Oskar (David Bennett), with a tin drum he receives on his third birthday, narrates his life relative to changes in German society. Because of the immorality he witnesses in the adults around him, he resolves to hurl himself down a flight of stairs in order to forever stay small. Using the drum and a scream that shatters glass, he persistently revolts against the adult world around him to combat their contemptable behavior. Finally, the rest of the film follows Oskar as he falls in love, watches members of his family die, and joins a troop of dwarfs that entertains soldiers, all the while learning more about the world around him and the responsibilities he must acquire.

Throughout the film, the drum symbolizes innocence for Oskar, which additionally represents what he desires. The adult world looks immoral and repugnant to him, so he clings to the drum through the whole film because it protects him. (However, throwing it into his father's grave at the end of the film is clearly a symbolic rite of passage indicating his choice to become responsible.) Although screaming children usually deserve a good spanking, his glass-shattering cries throughout the film are a protest to adults trying to steal his “innocence.” Aside from his shameless parents, even the adults in the world around him are in the midst of a huge revolution toward National Socialism. He tries to become a moral symbol through his drum, notably when his playing disrupts and confuses the Nazi band into a rousing rendition of Strauss’ “Blue Danube,” thereby quashing their evil-inspired rally. On the other hand, the film seems to be indicating that he is nowhere near as innocent as he pretends to be (in fact, he indirectly has a hand in the deaths of many of those family members!). Moreover, children in the film are still portrayed as having some bad qualities, which proves that no one is a saint. In addition, the film criticizes Oskar for not owning up to the responsibilities of growing up, and the final scene of the film indicates that it is necessary for him to “grow.”

Oskar is one of the most captivating narrators that I have witnessed in a film. His dynamic range of inflection sometimes elicits laughter, particularly when he speaks ferociously. He makes an interesting character, and director Schlöndorff’s blend of filmic fantasy and reality inspires his unbelievable personage. As a character, he is well-acted by Bennett, who, as an 11-year-old, takes his 3-year-old body for quite a bizarre adventure. Oddly, Oskar is intelligent from birth, though I have never met a person whom was able to narrate his own emergence from the womb (in a close-up, point-of-view shot certain to disgust viewers). Because of the film's somewhat fantastic representation, though, it does support his narrative reliablity and therefore trustworthiness; it furthermore arrests the interest of viewers who are easily taken by his fascinating character.

Overall, this film is completely brilliant. Though it is a bit long and occasionally inspires some time-checking, the story (based on the even longer book by Günter Grass) is generally interesting, evoking, and "in your face." It is also certain to surprise with its unabashed, unforgiving dive into deviant sexuality involving incest and children (which invoked the wrath of many, including an Oklahoma court with laws against child pornography and minors engaging in sexual activity). Most importantly, though, this is one shocking, moralistic film that adeptly takes a look at the bizarre life of a young boy who professes the indiscretions of grown-ups while living in a rotten society affected by Nazism.

April 27, 2008

The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel)

April 20, 2008

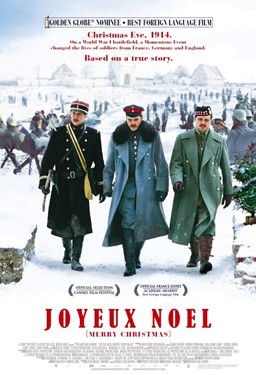

Joyeux Noël (Merry Christmas)

**** out of ****

**** out of ****

“Joyeux Noël” is a French film that inspires and promotes the idea of brotherhood, an important theme that not only relates to the fraternity of human beings, but also rejects war as a medium of resisting it. This anti-war sentiment is implied through many images in the film, which suggest the dehumanization and stupidity of men who enter the conditions of war. On the other hand, the other scenes insist on the brotherhood that men can derive whenever they realize that they are all the same. These themes are interpreted through an array of incredible stylistic and structural aspects under the direction of Christian Carion, actualizing “Joyeux Noël” as a modern French anti-war masterpiece.

“Joyeux Noël” centers on the real-life Christmas truce between the French, the Scottish, and the Germans during World War I and portrays characters such as the German tenor, Nikolaus Sprink (Benno Fürmann), his Danish opera star lover, Anna Sörensen (Diane Kruger), the German lieutenant, Horstmayer (Daniel Brühl), and the French Lieutenant, Audebert (Guillaume Canet), to encapsulate the humanity essential to its thematic heart. The film then depicts the events that follow as the characters and the three companies of soldiers share humanity in the crucial time of peace.

The structure of this film is perfect; “Joyeux Noël” readily combines many typical war-related thematic elements in a fresh way while featuring a great script and wonderful story. Christian Carion ably directs the film with a sense of pride that should leave viewers enchanted and interested during the Christmas cease fire. In addition, many stylistic aspects, such as lighting, sound, editing, and cinematography, blend perfectly together to achieve the conditions of war or of peace.

The film offers several examples that evoke the harmful effects of war, and the first example establishes a correlation between those effects and children. The opening scene features a slow dolly shot that moves toward children explaining WWI. This establishment stimulates questions of war’s effects on children, which leads viewers to realize the effects of war on younger generations. Because of the superimposition of each new child over the next, it’s like the same child speaking, though his appearance changes and his speech represents a different language. This clearly underlines the human aspect of the film. Later in the scene, the long dolly shot passes through the map in the room, and an aerial shot rushes over lands with exceptionally slight differences but notable similarities. In essence, the shot unites those lands, contending that on some level, even the land on which humans live is the same.

Death is always a consequence of war, and the film establishes that connection quickly. Death is highlighted when the Scottish man opens the door of the church at the beginning of the film, extinguishing all of the flames the priest had lit. Using a selective focus, the shot foreshadows the death (or the extinguishment) of men who go to war and prompts the overall negative view of war in general. On the other hand, that particular shot of smoking candles fades to lit candles in another room while a diva sings an operatic tune. Its implications define music as life and signify its importance in comparison to war, which explicitly infers death.

In addition to death, the film wants to implicate several more negative consequences of war for viewers, including chaos and the dehumanization of man. During the great battle early in the film, a handheld camera captures a tracking shot of the men in the trenches and on the battle and exposes the great realities of the war, particularly on the chaos involved. Using a weepy orchestral piece over the battle, the scene prominently features quick cuts and intensely loud sound effects amidst the chaos. In fact, one important attribute of the scene is crosscutting that includes shots of men and their artillery, comparing one to the other, signifying that in war, man is like, or less than, his machine. The machine robs him of his humanity and turns him into a less than human object.

The film juxtaposes war to Christmas in different ways, but intentionally to promote the concepts of peace and brotherhood. As the eve before Christmas falls, the soldiers are in their respective trenches as a Scotsman’s bagpipes erupt over the crystal silence. While he plays, the German opera stars begin to sing “Silent Night” against his song, in a sort of “battle” between the two. Eventually, the Scotsman plays the song while the Germans sing, uniting the two and creating the harmony that is essential to the film. There are several instances of two different musical cultures being united in the film, and the codes implied by their unity indicate the brotherhood significant to the film. Finally, another effect of Christmas is when Sprink crosses the snowy battlefield in an extra long shot, singing and carrying the Germans’ Christmas tree; the action of singing connects back to the idea of life while the tree becomes a symbol of peace and unity.

While incredibly dramatic and mind-opening, the film does contain some humorous elements, such as Felix/Nestor, the cat who prances through both trenches like a double agent while signifying how he is the same cat no matter what name he has. Even this one example signals the critical theme of “Joyeux Noël”: We are all the same but with different names, and thanks to brotherhood, peace can be attained. While one of endless anti-war films out there and unlike classic films like “Paths of Glory,” which is more in-your-face in its protests, essentially, Christian Carion’s “Joyeux Noël” succeeds in its propagation of peace and will surely become a film classic in years to come.

April 17, 2008

Snow Angels

** out of ****

** out of ****

The promotional poster for David Gordon Green’s “Snow Angels” says “Some will fall, some will fly,” and as far as the film is concerned, I am inclined to concur with the former. With the depression and intense dramatization that surrounds the breakdown of families, I was predisposed to initially compare the film’s circumstances to such American film classics as “Ordinary People” or “American Beauty,” but ultimately, “Snow Angels” is a pale light to either of them.

In the film, a teenaged band geek named Arthur (Michael Angarano) watches his parents split up while his co-worker Annie (Kate Beckinsale) struggles with her depressed, estranged husband, Glenn (Sam Rockwell), in small-town, U.S.A. Meanwhile, Arthur finds his first love in quirky new girl, Lila (Olivia Thurby), and Annie seeks comfort in the arms of Nate (Nicky Katt) whose lothario-like ways eventually pull apart all of his relationships, including his marriage. Eventually when Annie’s daughter goes tragically missing, everything falls apart and nothing is the same again.

On paper, this plot sounds rather complicated and intriguing, but in reality, it is neither. Segments of “Snow Angels” display how director Green is out-of-touch with so many aspects of his film, particularly in the area of character development. For example, Arthur is a relatively believable teenager until he becomes a caricature—his stash of Heineken and his bong connote a recklessness that is synonymous with adventurous youth, but obviously their random insertion tears away from the construction of Arthur’s character. Even Glenn becomes the caricature of one of those crazy people who advocates religious tapes while harboring insanity within. In addition, the collapse of the house of stacked photos that Arthur’s mother had been slowly creating conspicuously represents her fraught psyche. I think that Green cuts corners in his character development by using simple devices like these in order to reveal something about each character, meaning they are intended to be representatives of something to be believable, but this denotes a lack of ingenuity in the screenplay, and with its emphasis on character interaction, poor character development is something from which it should not suffer, but alas, it does.

One important scene worth mentioning reveals a crucial theme of the film and does indicate some of its intelligence. When Lila shows Arthur her first impressions of the town with the photos from her album, her photos exhibit several locations around the town that are covered by the film’s perpetual snow. The beauty and innocence indicated by the snowy scenes do not register with Arthur, who says he can hardly recognize any of the places in the photos even though he lives among them all. The photos are notably idealistic, as the snow in nearly every scene of the whole film is dirty, and the beauty and purity indicated by the photos are truly nonexistent. Obviously the idea of snow contrasts with the bleakness paramount to the film and proves the unrealistic ideal of the photos in comparison with the murky reality of the town. With an appropriate thematic representation like this, Green ably proves that his screenplay does hold up despite other failings that I have established.

In essence, the film does express moments of complete and utter magic, but at other times, the film descends to the levels of Lifetime movie hell. Only through the genuine acting of the main characters and moments of clever writing is the film saved from that damnation.

“Snow Angels” is playing now at the Belcourt Theater.

Originally published in the April 17 issue of Versus Magazine: Entertainment & Culture

April 10, 2008

Paranoid Park

** ½ out of ****

** ½ out of ****

“Paranoid Park” is a moody film that interestingly and endlessly toys with style but unfortunately concludes lacking in structure. It is an experimental film that decadently enjoys the use of discontinuous editing, cinematography, and sound in its presentation. Set in Oscar-nominated director Gus Van Sant’s own backyard of Portland, Oregon, the film brings wonder to the seemingly uninspiring town with one place that enlivens its youth. Oddly enough, the titular “paranoid park” becomes an idea that is hardly transcribed into the film; although its appearance serves as the force that leads to the skateboarding protagonist’s misfortune, it hardly attributes paranoia to his psychosis, as he becomes relatively passive until the film’s end.

In the film, Alex is a 16-year-old skateboarder who accidentally kills a security guard one night. The rest of the film follows him through what happens afterward while he writes all of the preceding and transpiring events in a journal.

The whole film is derived from the perspective of this teenaged boy; at the beginning, as he writes, he apologizes because he knows his thoughts will come out-of-order, which reflects on the film, as the narrative disjunctively presents itself using discontinuous editing and an alternative-to-narrative structural system. Because the film centers on the idea of viewers following the events that transpired, several shots are re-presented and do inspire viewer participation since they actively question the discrepancy between actual circumstances and what Alex claims happens.

For “Paranoid Park,” Van Sant returns to the sort of rebellious youth for which he is well-known for interpreting in film. Relating to his oeuvre, including “My Own Private Idaho,” rebellion recurs as an important theme, as Alex’s action of striking the security guard with his skateboard while on the train signifies rebellion against authority. Alex, coming from the skateboarding subculture, is forced to represent every aspect of the socially misunderstood group, so his every action is judged. I am amazed at how Van Sant captures the perspective of a teenaged boy, and it is noticeable how much he cares for his protagonist. Van Sant is notable for his penchant for exploring misunderstood characters, and his take on apathetic Alex is no different.

The film features incredible cinematography, editing, and especially sound. Sound and lighting often display the inner psyche of Alex. One incredible example of sound is the shower scene where the soft sound of the running water slowly builds to the sound of torrential rain, which expresses the tension and anxiety building in him. Though sound does tend to interpret Alex’s mentality, there are instances of anempathy, where the music is driven by external forces trying to affect him, but they usually do not, as the sound or music changes back to his interpreted state-of-mind. It is interesting to note how sounds in his environment are often louder than normal, like there is meticulous attention being paid to them, oddly contrary to Alex’s typical apathetic opinion of his environment. Besides sound effects, Nino Rota’s music from “Juliet of the Spirits” is used quite frequently, and its use seems to be related to the power of Alex’s subconscious, like Giulietta in Fellini’s 1965 film.

Cinematography in the film is characterized by interesting mobile framing, including relatively unrelated scenes of skateboarders, who sometimes fill the voids between shots. With an amateur feel produced by a handheld, low-grade video camera, these long shots offer the depth of beauty, realism, and understanding that Van Sant wants to provide to viewers who do not comprehend skateboarders. Framing has another effect in the film, as one of my favorite shots is the pan and zoom that locks Alex in the frame during his interrogation, isolating him. This presents isolation as a key theme because it visually facilitates understanding of Alex’s situation—he is quite alone in all that is happening to him, with only himself to rely upon.

Because the film is presented in a disconnected order and the narrative is sometimes relentlessly slow, hardly anything happens of significance; thus, it ultimately provides no narrative pay-off. The film’s plot essentially revolves around the accident that results in the security guard’s death and some on what happens afterward. The ending is incredibly anticlimactic, but it is to be expected, particularly since the narrative drifts and Alex, through whom the film is portrayed, expresses unbelievable apathy to it all. In fact, he is apathetic to almost everything—his friends who jibe him about having sex, his sexually-driven cheerleader girlfriend, his caring friend, and his relatively non-existent parents. Alex’s parents are usually obscured or out-of-focus, demonstrating their lack of support or meaning in his life. However, his father is presented only once when he offers help, of which Alex refuses. Alex is a solitary being in the film, and his rebellion and passivity are his defining traits.

Though Van Sant’s effort on “Paranoid Park” is contrary to the apathy of his protagonist character (but not the actor—a solid effort for a first-timer) and characterized by his love for those who are misunderstood, the film’s plot ultimately negates his effort and offers viewers little. It is interesting, but is just not inspiring.

It is necessary to mention that the film is a tad gruesome, but only when the security guard is explicitly seen being run over on the railroad track.

“Paranoid Park” is now showing at the Belcourt Theater.

Originally published in the April 10 issue of Versus Magazine: Entertainment & Culture

April 3, 2008

Who Framed Roger Rabbit

**** out of ****

**** out of ****

"Who Framed Roger Rabbit" is an extraordinary film, riskily combining live action and animation, but coming off as pure perfection. Nearly all of the material and inspiration is borrowed, but "Roger Rabbit" blends it creatively and well. In addition, mixing all of the well-known cartoon characters from different studios, including Betty Boop, Daffy Duck, and Droopy Dog, is a miracle in itself. Later films such as "Space Jam" have not been able to replicate the power that the innovative design of this film successfully touts.

The film is based on the 1981 novel, "Who Censored Roger Rabbit?," by Gary K. Wolf. In the film, Roger Rabbit is a cartoon character who worries that his wife, sexy Jessica Rabbit, is playing "pattycake" with someone else. When that person turns out to be Toontown and Acme Company owner Marvin Acme, it all hits the fan once Acme turns up dead and Roger becomes the prime suspect. Eddy Valliant (Hoskins), the detective who took the tell-all photos of Jessica and Acme, is Roger’s last hope for clearing his name and uncovering the real killer and the larger devious plot.

Bob Hoskins is fantastic as the grumpy detective who “don’t work for toons!” Titular character Roger Rabbit is an entertaining alternative to everyone’s favorite, carrot-chompin’ Bugs Bunny. With no contest, the highlight of the film is one Jessica Rabbit, who exudes sexuality from her sultry eyes to rich rouge hair to the slit in her dress sliding up her thigh to her large breasts. She says, “I'm not bad. I'm just drawn that way.” She is the epitome of the film noir femme fatale.

Film noir itself is the greatest inspiration for this film, from the detective protagonist to the femme fatale to the mystery and intrigue. The film obviously draws on such classic films as "The Maltese Falcon" (dead partner) and "Chinatown" (sales of local resource—there water, here the train system, and the photos showing infidelity).

Particularly because of the cultural coding established by film noir, the 40's-inspired art direction is fantastic and delightfully appropriate. Sitting and hand-drawing every cell of animation must have been tedious, but the finished product shines. Other aspects of the film worth mentioning include the sound and sound mixing, which were fantastic. Robert Zemeckis also does a fabulous job behind the camera, bringing this cartoon-laden mystery to life. The only slight drawback worth mentioning is Alan Silvestri’s score, which sticks out like a sore thumb because everything about it screams "Back To The Future." However, this was a more obvious problem in his earlier work. The score is enjoyable nonetheless.

The film’s theme seems to be a clash between old and new. One example is the direct comparison and contrast between the older and newer ‘toons, notably Betty Boop and Jessica Rabbit. Though Betty proudly claims, “I’ve still got it,” the men in the bar quickly direct their attention to the alluring gaze and erotic frame of Jessica when she appears. Another example is how Judge Doom attempts to erase Toontown and create freeways with his Cloverleaf Corporation—this could again be another direct example of the old phrase “out with the old, in with the new.” Besides the narrative, the film itself brings about the heralding moment of film since it so astonishingly combines live action with animation as never before.

This film is a wonder and a favorite. Everything about this film is outstanding because it venerably draws on many sources of classic film and animation and creatively delivers distinct, awe-inspiring stylistic elements. Roger Rabbit truly deserved its numerous Academy Awards, including Best Film Editing, Sound Effects Editing, and Visual Effects, and a Special Achievement Award for Animation Direction. Audiences will laugh, but they will also be captivated with the suspense. This zany masterpiece does target audiences of all ages, but adults will capture the innuendo better. Everything about this film is flawless.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)